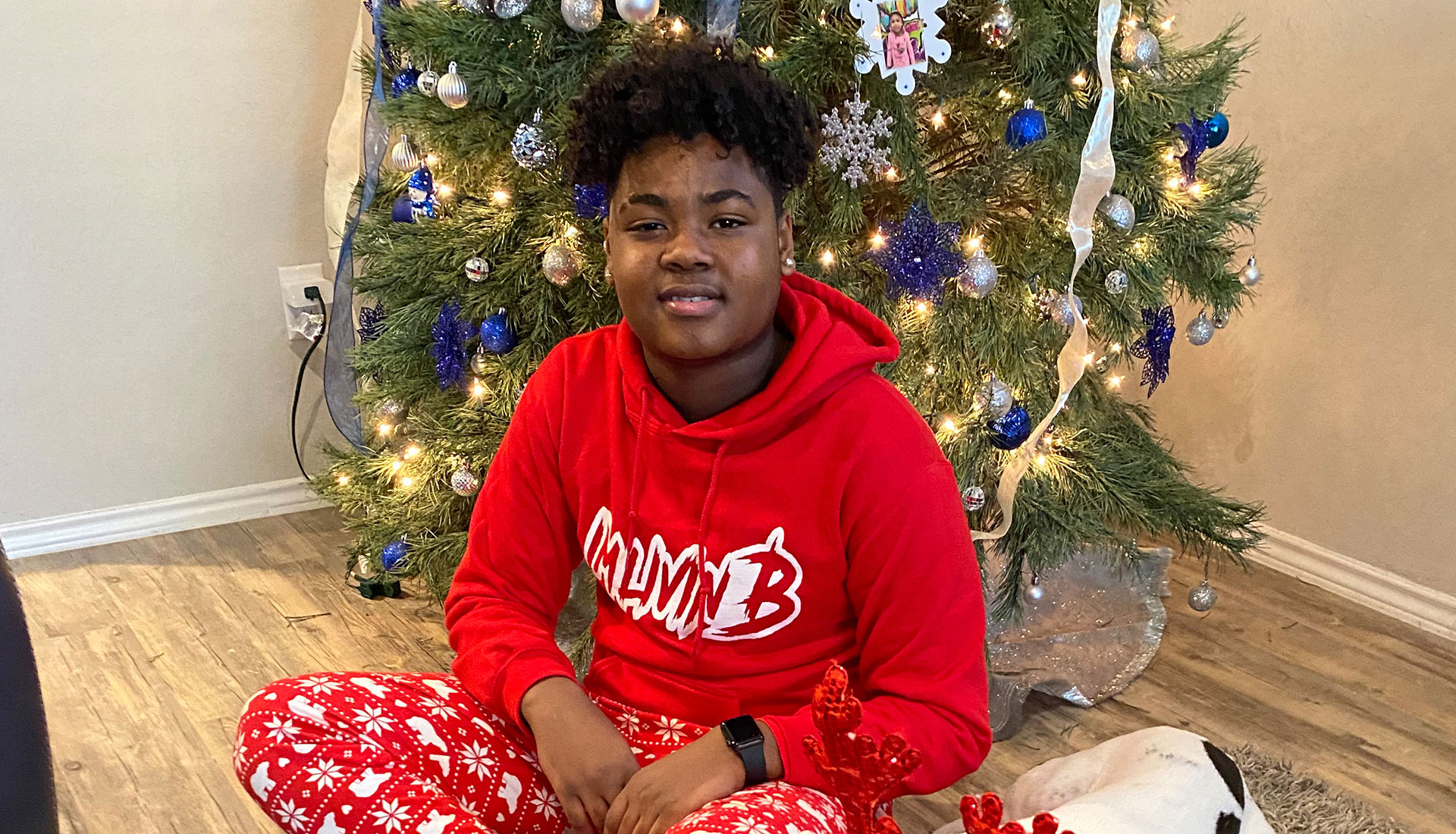

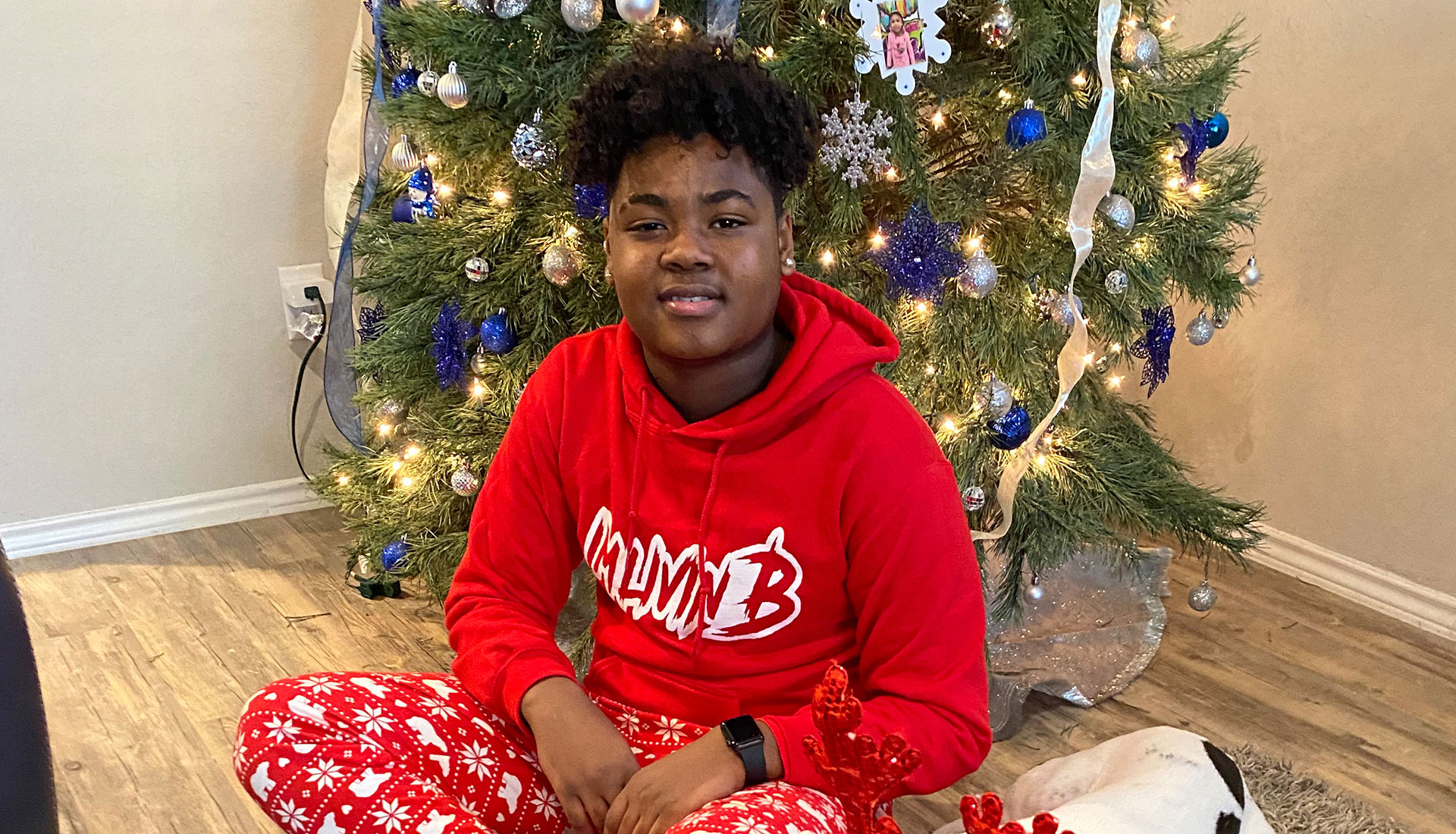

Christmas 2020 was a wonderful holiday for Shemar Felton’s family as they celebrated the recent recovery of Shemar, 15, and his mother, Loreena Ekong, from COVID-19. They had no idea that the next day Shemar would begin a fight for his life.

The day after Christmas – three weeks after he tested negative for COVID-19 – Shemar woke up with a temperature of 103 and a bad headache. Over the next five days, Shemar was examined at two urgent care centers and three hospital emergency departments. He was diagnosed with possible colitis, a virus and dermatitis. Each time he was sent home.

By New Year’s Eve, Shemar had a 104 temperature, chest and neck pain, and a rash covering his entire body.

“He was completely delusional. His heart was pounding out of his chest. His eyes were red and inflamed. He was just falling apart,” Mrs. Ekong said.

An echocardiogram at Texas Children’s Hospital The Woodlands showed that Shemar’s heart was functioning below normal. He had inflammation in his heart, eyes, skin, intestines and kidneys. Emergency medicine physicians at Texas Children’s Hospital The Woodlands sent him by ambulance to Texas Children’s campus in the Texas Medical Center, where he was admitted to the Cardiac ICU.

Texas Children’s physicians diagnosed Shemar with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a rare, dangerous condition that strikes some children four to six weeks after a mild or asymptomatic COVID-19 infection. Researchers publishing in the New England Journal of Medicine estimated two MIS-C cases per 100,000 children.

“Their constellation of symptoms is usually high fever, fatigue, abdominal pain, rash and often abnormalities with blood counts and inflammatory marker levels,” said Eyal Muscal, MD, MS, chief of rheumatology at Texas Children’s and associate professor of pediatrics-rheumatology at Baylor College of Medicine.

“We’ve had probably two-thirds of these kids end up in the ICU in shock, or with dangerously low blood pressure. The older the children are, the more chance there is of severe inflammation, not just in the blood vessels, but the actual heart muscle. It can be life threatening if not caught early enough and inflammation appropriately dampened,” Dr. Muscal said.

Shemar fit the profile for MIS-C. At Texas Children’s, patients with this condition have ranged in age from 9 months to 18-years-old. Like Shemar, a very large percentage have been from minority racial and ethnic groups, for reasons researchers have not yet been able to identify. There are slightly more males than females.

By the end of 2020, approximately75 MIS-C patients were treated at Texas Children’s three Houston-area hospitals. By March 2021, the number was up to around 125.

“When we recognize that MIS-C is the problem, we start treating in two ways,” said Tiphanie P. Vogel, MD, PhD, assistant professor of pediatrics-rheumatology at Baylor.

First is supportive care – blood pressure support, possibly intubation, management of critical parameters to support the patient during this critical time.

“At the same time, we start anti-inflammatory medicines as fast as possible. We have been using medications that have a quick mechanism of action, so they work quickly to quench all of this hyperinflammation. As the patients get better, they need less and less support. After only several days, most become well enough that they go to a regular patient floor,” she said.

As with Shemar, the average length of stay in the hospital is nine days.

“It really does require teams of doctors working together,” Dr. Muscal said.

Collaborating on care of MIS-C patients are physicians from:

Pathology, in particular, has made a huge contribution to treatment and general knowledge.

“We have antibody results from pathology faster than any other hospitals that I know about. Colleagues were telling me, for a while it was taking weeks to get their antibody tests back, and we get them in hours,” Dr. Vogel said.

Pediatric cardiologist Kristen Sexson Tejtel, MD, PhD, MPH, and pediatric rheumatologist Eyal Muscal, MD, MS, collaborate on care and followup for COVID-19 and MIS-C patients.

Pediatric cardiologist Kristen Sexson Tejtel, MD, PhD, MPH, and pediatric rheumatologist Eyal Muscal, MD, MS, collaborate on care and followup for COVID-19 and MIS-C patients.

A week or two after discharge from the hospital, MIS-C patients return to Texas Children’s for follow up in a newly created multidisciplinary clinic. A cardiologist and a rheumatologist together examine the children, ask questions about how they are doing and review lab results and other tests. The cardiologist continues to follow up at gradually longer intervals.

“The plan is to follow them at least annually for five years because the disease is so new that we still don’t really know what to expect,” said Kristen Sexson Tejtel, MD, PhD, MPH, pediatric cardiologist at Texas Children’s and assistant professor of pediatrics-cardiology at Baylor. ”The ones we have seen for their follow-ups at this point are doing well.”

Dr. Sexson Tejtel also established another new clinic in collaboration with Silvana M. Molossi, MD, PhD, pediatric cardiologist at Texas Children’s and associate professor of pediatrics-cardiology at Baylor, who directs a Texas Children’s sports cardiology clinic. Under a return-to-activity protocol that they developed, all children are checked and tested thoroughly for heart problems after COVID-19 and MIS-C, before clearance to return to sports.

At discharge, Shemar’s heart function had improved to the normal range. However, patients are not cleared to return to sports for several months after cardiac inflammation.

“He’s a 15-year-old athlete. He’s not used to just sitting still, so he’s having a hard time with that,” Mrs. Ekong said. “But he’s on the road to recovery, and we are confident that the treatment is going to get him where he needs to be.”

Besides MIS-C and potential heart problems, some children have other chronic complaints after COVID-19:

“This is different from post flu. Post bad flu, you don’t feel great for a while, but a week or two out, you’re feeling fine. Kids are six months or more out from COVID, and they’re still not feeling right,” Dr. Sexson Tejtel said.

Dr. Sexson Tejtel says apathy is a troubling symptom among certain patients.

“It seems to be more common in teenagers. Grades change because of the lack of initiative, the lack of wanting to be part of things. In adults, doctors have been using a lot of exercise and physical therapy to treat it, which I’ve been trying, sometimes with good success, sometimes not,” she said.

“I think there’s still a lot of information we don’t know yet about COVID and MIS-C. We’re learning as much as we possibly can about these kids as quickly as we can,” Dr. Sexson Tejtel said.

The interdisciplinary team at Texas Children’s meets two times a week to discuss process and procedural issues, with less frequent meetings to discuss research including:

The collaborative work in which the team is engaged crosses geographical borders as well, including:

Working together across disciplines, the Texas Children’s/Baylor team continues to help MIS-C and COVID-19 patients return to health locally and around the world.