Rapid changes in the COVID-19 pandemic during 2021 made dealing with the virus seem like a roller coaster ride.

“We started the year with the buoyant optimism of having a new technology enabling vaccines to be developed during a pandemic in less than a year, something we’d not seen before in the world,” said James Versalovic, MD, PhD — Pathologist-in-Chief at Texas Children’s Hospital and Vice Chair for Molecular Pathology at Baylor College of Medicine — who also served as Interim Pediatrician-in-Chief at Texas Children’s during most of 2021.

Beginning in January 2021, Texas Children’s Hospital administered vaccines to the workforce and to patients aged 16 and above, including those in the Pavilion for Women and the Adult Congenital Heart Disease Program.

“There was great momentum. But we also were in the midst of a winter surge. So there was optimism balanced with caution and plenty of concern about the ongoing pandemic. We were at best partially vaccinated, and we had more workforce infections than we did at any other time in 2021,” Dr. Versalovic said.

Texas Children’s based its pandemic response on three pillars:

The first COVID-19 cases at Texas Children’s were in the spring of 2020.

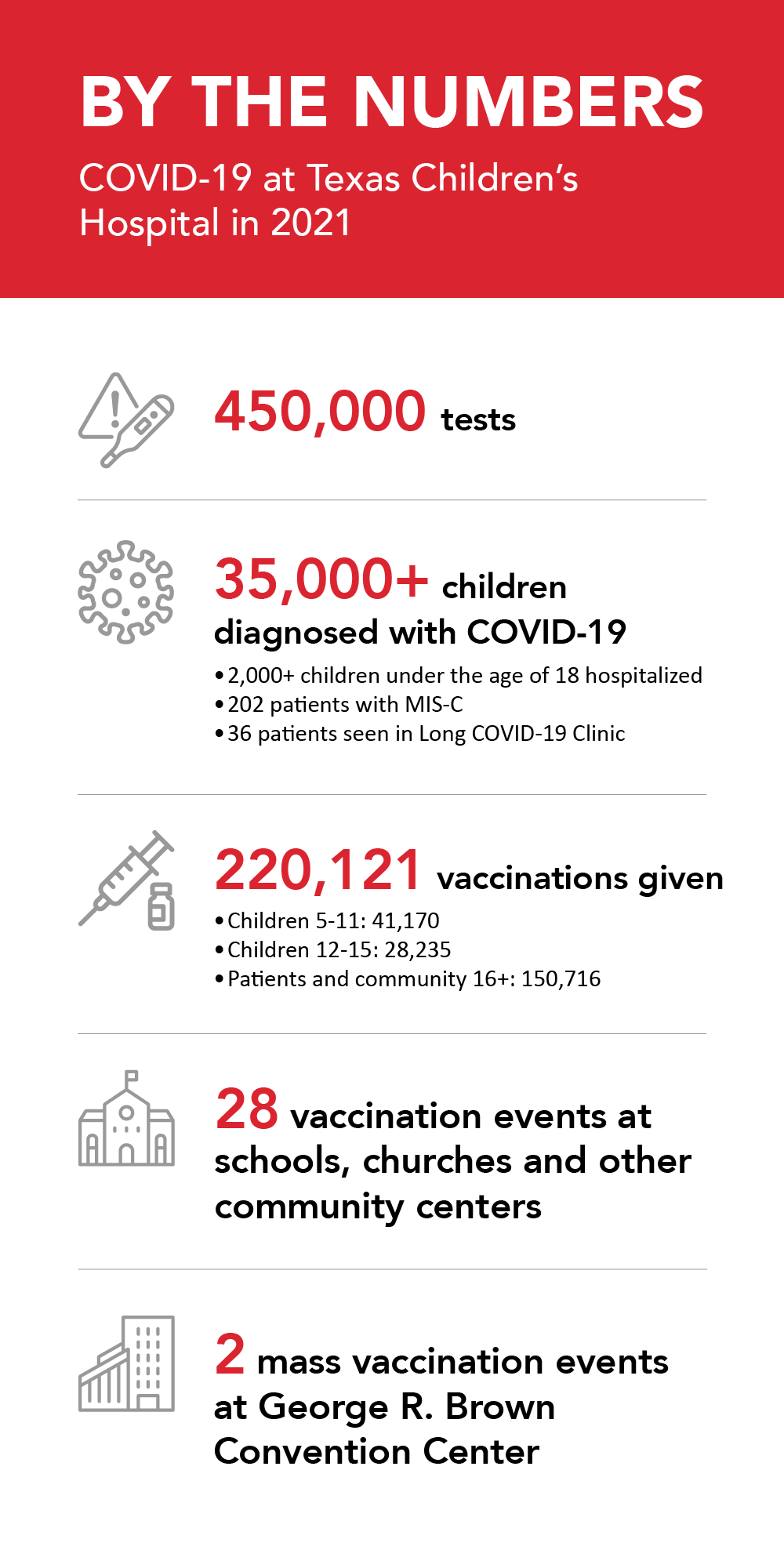

The Department of Pathology ran almost 450,000 tests and diagnosed well over 35,000 children with COVID-19 during 2021. More than 2,000 children under the age of 18 required hospital care, hundreds in critical care.

Diagnosing multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a life-threatening complication following COVID-19, is especially challenging because it has overlapping symptoms with other inflammatory diseases, notably:

Appearing about two to six weeks after even a mild case of COVID-19, MIS-C causes hyperinflammation and can affect vital organs, most seriously the heart.

The similarities between MIS-C and Kawasaki disease, a well-known childhood vasculitis – blood vessel inflammation – were clear to clinicians from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. By late 2020, articles had appeared in medical journals trying to differentiate between MIS-C and Kawasaki disease, which affects primarily younger children with fever, rash and inflammation of the coronary vessels. MIS-C often affected older children and with more severe myocarditis – inflammation of the heart muscle.

Determining whether a child has MIS-C or endemic typhus, a bacterial infection transmitted by fleas in tropical and subtropical regions, including Houston, proved more elusive.

“MIS-C and endemic typhus look very similar clinically, but they have completely different treatments,” said Tiphanie Vogel, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor of Pediatrics-Rheumatology at Baylor. “You could do antibody testing for typhus, but that test doesn’t come back for days.”

To obtain a diagnosis and begin appropriate treatment within hours, instead of days, Dr. Vogel proposed a collaborative project with Professor Ioannis Kakadiaris, PhD, in the University of Houston Computer Science department. Funded through a National Institutes of Health grant to the Baylor-Texas Children’s Department of Radiology to study COVID-19 in children (principal investigator, Ananth Annapragada, PhD), the project used artificial intelligence and machine learning to train the computer to tell the two diseases apart.

The investigators refined the program so that now it can use just 11 features, such as rash, number of days of fever, and easily obtainable lab test results, to tell the difference between MIS-C and typhus with greater than 90% accuracy. Calling it the MET score, which stands for MIS-C versus Endemic Typhus, the team is working to make the calculator available worldwide in an online medical calculator app.

By 2021, national and international recommendations emerged for treating COVID-19, and Texas Children’s established internal standards of care.

“Compared with the first summer surge in 2020, when we were struggling with new therapies, we became much better at treating COVID-19 and being comfortable with it,” said Amy S. Arrington, MD, PhD, Medical Director of Texas Children’s Special Isolation Unit and Chief of Global Biologic Preparedness in the Department of Pediatrics at Baylor.

The organization adapted to take care of the patients, who were sometimes critically ill.

“When it comes to hyperinflammation due to primary COVID-19 or MIS-C, treatment really does require teams of doctors with different expertise working closely with bedside nurses,” said Eyal Muscal, MD, MS, Chief of Pediatric Rheumatology at Texas Children’s and Associate Professor of Pediatrics-Rheumatology at Baylor. “The ability of teams to work seamlessly together has been one of the few blessings of the pandemic. By 2021, we had a much better sense of diagnosis and of everyone’s role on our teams, knowing that the best outcomes are with timely interventions.”

The Department of Pediatrics Divisions of Emergency Medicine, Hospital Medicine and Critical Care were linchpins in the treatment of children hospitalized with COVID-19. Other members of interdisciplinary care teams included pediatric subspecialists in such areas as Rheumatology, Cardiology, Infectious Disease, Hematology and Pulmonology.

“We’ve had remarkable outcomes. That’s largely thanks to the collaboration between our medical staff in Pediatrics and our colleagues in Nursing,” Dr. Versalovic said.

Texas Children’s likely has cared for the largest number of children with MIS-C at any single children’s hospital in the country — 202 patients just in 2021. So far, the heaviest stress on the hospital system occurred during the Delta surge beginning in August 2021, when MIS-C cases surged soon after new primary COVID-19 cases. The Omicron variant caused another massive surge of COVID-19 infections beginning in late 2021, but it did not cause a surge in MIS-C.

For patients with MIS-C, the Texas Children’s teams developed standard medication protocols that depended on severity of illness and cardiac involvement. These protocols used a host of anti-inflammatory interventions based on presentation. Many patients received early intravenous corticosteroids.

“We developed clear criteria for who gets additional medications, such as immunoglobulin infusion when there are specific cardiac features of inflammation,” Dr. Vogel said.

“For more severe cases, where there was shock or an admission to the ICU, we used anakinra, a biologic medication that blocks a potent inflammatory pathway. We have found this medication to be very effective very quickly,” she said.

Used by rheumatologists to control inflammatory diseases, anakinra is most often available to treat children in hospitals that have pediatric rheumatologists and a large number of patients with childhood inflammatory conditions. Due to its expense and the subspecialty expertise needed to manage anakinra, the medication is not available to treat children in hospitals in many areas of Texas and some other states.

“We’ve seen a number of cases where children received the other medicines at another hospital, didn’t improve, and are transferred to us. We start them on anakinra, and they have notable improvement within hours,” Dr. Vogel said.

In follow-up, Texas Children’s pediatric patients diagnosed with MIS-C are doing well, and most have returned to normal activities.

For patients with long COVID-19, symptoms persist for many months after the initial infection. They may have cardiac, neurologic or pulmonary complications that prevent a return to normal activity. Texas Children’s Long COVID-19 Clinic treated 36 patients in 2021.

Children with long COVID-19 often appear to have dysautonomia, a disorder of the autonomic nervous system, which regulates nonvoluntary body functions, such as heart rate, breathing and digestion.

“We started using some of the treatments for dysautonomia,” said Long COVID-19 Clinic Director Kristen Sexson Tejtel, MD, PhD, MPH, Pediatric Cardiologist at Texas Children’s and Associate Professor of Pediatrics-Cardiology at Baylor.

“There are many different treatments that may work, but what works for one individual doesn’t necessarily work for the next. Unfortunately, long COVID-19 can last far longer than we want, but usually we can help with symptoms. Treatment is still evolving,” Dr. Sexson Tejtel said.

For example, Neurology and Neuropsychology have found that stimulants may help with the fatigue and difficulty paying attention that often accompany long COVID-19. Other subspecialties at the Long COVID-19 Clinics are Neurology, Physical Therapy, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Psychology, and Pulmonology.

“Many parents tell us that what helps the most is that we recognize that their child has a problem, that we listen and that we are trying to figure out the best ways to treat it,” Dr. Sexson Tejtel said.

When the pandemic spread to the Houston area in 2020, patients suspected of having COVID-19 were transported to the Special Isolation Unit at Texas Children’s Hospital West Campus. Dr. Arrington led development of infection control protocols and training in other Texas Children’s facilities, as well.

“By 2021, we decided that keeping COVID-19 patients congregated together in special COVID-19 units was no longer necessary,” Dr. Arrington said. “As long as we’re careful, wear the right personal protective equipment (PPE) and use good hand hygiene, they don’t have to be cohorted.”

PPE with COVID-19 patients has not changed since the beginning of the pandemic. It still includes the well-fitted N95 mask, gown, gloves and eye protection. In other areas of the hospital, staff continue to wear masks.

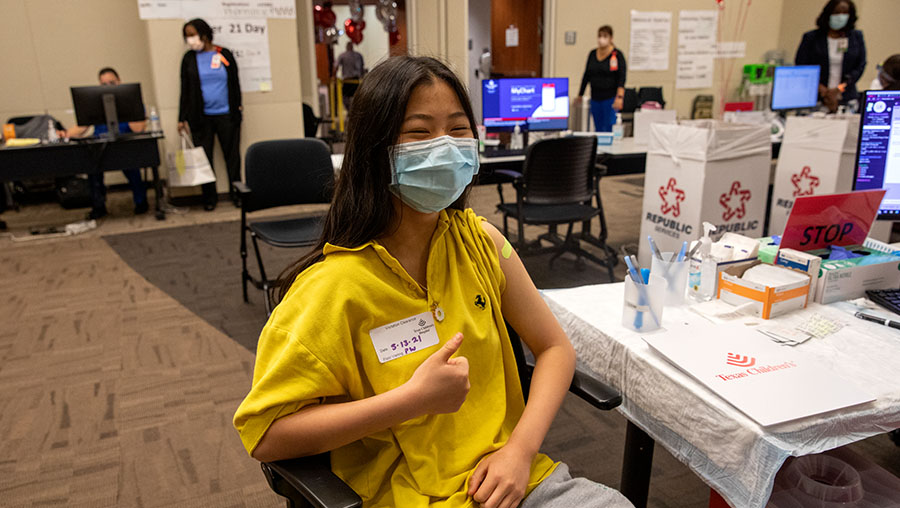

The 2021 winter surge of COVID-19 was followed by an extended lull in the spring, providing a chance to focus on prevention and the launch of vaccinations for 12- to 15-year-old children in May. Many younger adolescents were just gaining access to the vaccine in the summer as the more contagious Delta variant hit.

Another lull occurred in October and November, followed by the even more contagious Omicron variant in December. At that time, vaccinations had just begun for 5- to 11-year-olds.

“It was a race between vaccines and variants during the entire year,” Dr. Versalovic said.

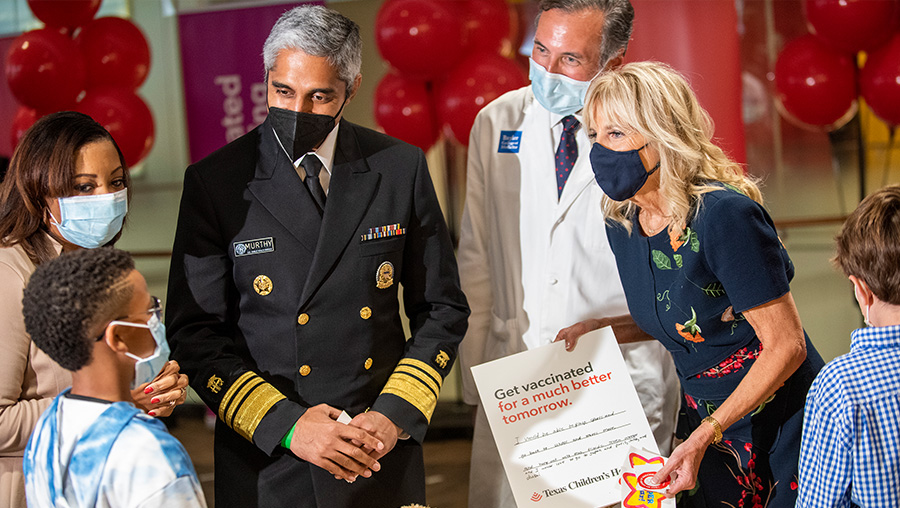

While production and distribution of vaccines ramped up, Texas Children’s appointed a COVID-19 Vaccine Task Force, co-chaired by Julie Boom, MD, Director of Texas Children’s Immunization Project and Professor of Pediatrics at Baylor; and Jermaine Monroe, Vice President of Texas Children’s Human Resources. Task Force members included physicians, nurses and executives from diverse specialties and backgrounds.

Until the beginning of May 2021, supplies of vaccines were limited. Federal and state governments dictated that the first vaccination priority was to secure the safety of health care workers so they could care for others.

Once vaccinations no longer were constrained by limited supplies, Texas Children’s expanded outreach into the community. Health care providers volunteered to help educate and reassure individuals who were hesitant to receive vaccines.

“We conducted informational town halls for persons of multiple groups, whether it was based on race and ethnicity or a medical condition like pregnancy,” Dr. Boom said. “We also created multiple presentations completely in Spanish for people who recognize Spanish as their first language.”

Texas Children’s hosted 28 events at schools, churches and other community centers in areas that were historically underserved. The hospital and the city of Houston partnered in two mass vaccination events at the George R. Brown Convention Center.

“We made vaccination easy and accessible not just to children, but also to their parents and to anybody eligible to get a vaccine,” Monroe said. “These events have been well received. When Texas Children’s goes into communities, we are a trusted entity. At some sites, we’ve had over a thousand vaccinations.”

In total, Texas Children’s administered 220,121 COVID-19 vaccinations in 2021.

As vaccinations increased during 2021, some cases of vaccine-related myocarditis appeared, particularly in teenage and young adult males.

“Most of our cases of vaccine-related myocarditis have been mild, and we continue to encourage vaccination for children,” Dr. Sexson Tejtel said. “If you get myocarditis from COVID-19, it’s much worse and much more likely to cause long-lasting effects than a post-vaccine inflammatory process.”

Dr. Vogel was first author of a high-impact paper published in the journal Vaccine in 2021 to outline criteria for evaluating whether MIS-C develops after vaccination. Other Baylor-Texas Children’s faculty among the multidisciplinary, international group of co-authors include Dr. Muscal; Flor Muñoz, MD, MSc, Associate Professor of Pediatrics-Infectious Disease; and David Hilmers, MD, EE, MPH, MSEE, Professor of Pediatrics.

“Further research has shown that vaccination protects pediatric patients from developing MIS-C,” Dr. Vogel said.

The Baylor-Texas Children’s Pediatrics team collaborated with a pediatric rheumatologist in Italy to publish a 2022 case series in JAMA Network Open on vaccinating children who had recovered from MIS-C. None of the patients developed a recurrence of MIS-C, myocarditis or any hyperinflammatory condition after getting the COVID-19 vaccine.

From the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Baylor-Texas Children’s multidisciplinary teamwork contributed to resilience and the ability to adapt rapidly to changes in the virus and its effects. Physician and nursing leaders, executives, and faculty across the subspecialties of Pediatrics came together effectively in short timeframes that challenged every large health care organization in the United States.