The stress of the COVID-19 pandemic has been hard enough for adults. What about for children and adolescents who have not developed as many coping skills?

The pandemic has been rough on kids’ mental health. In Texas Children’s Hospital Emergency Centers, the number of children experiencing mental health crises has increased from about 100 children per month to 400 or more children per month, according to Karin Price, PhD, Chief of Pediatric Psychology at Texas Children’s and Associate Professor of Pediatrics-Psychology at Baylor College of Medicine.

In 2021, behavioral health was the most frequent reason for referral for outpatient care across the Texas Children’s system.

Growing numbers of mental health emergencies have included:

Dr. Price outlined some pandemic-related factors that contribute to mental health issues:

“The pandemic has had tremendous impacts on parents, adults and families — everything from economic concerns, job loss, loss of social supports in the community and isolation from extended family members. When parents are stressed and not coping well, their children tend to experience negative impacts,” Dr. Price said.

“We also are in a time when kids are experiencing a lot of grief and bereavement because of the loss of family members as a result of the pandemic.”

By late 2021, more than 140,000 children in the United States had lost a significant caregiver, according to a joint statement by the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and Children’s Hospital Association. Declaring a national state of emergency in children’s mental health, the organizations advocated increased access for all families and children to screening, diagnosis and treatment that addresses mental health needs.

Texas Children’s Chief of Psychology Karin Price, PhD, testified to the Texas House Select Committee on Youth Health and Safety about the increase in patients with mental health needs during the pandemic.

Texas Children’s Chief of Psychology Karin Price, PhD, testified to the Texas House Select Committee on Youth Health and Safety about the increase in patients with mental health needs during the pandemic.According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among U.S. girls ages 12-17 increased 51 percent from early 2019 to early 2021. Extreme anxiety and depression can cause children and teens to think about or plan suicide.

Texas Children’s Department of Pediatric Psychology takes a family-based approach to empower parents to help their children who are anxious or depressed.

“The first thing we do is develop a safety plan,” Dr. Price said. “We work with the child and the family to identify triggers or early warning signs of emotional distress, so that we’re not getting into that crisis mode. Then we talk about coping. What can you do that will distract you from some of your negative thoughts and feelings? Who are the friends and adults in your life with whom you can talk?”

Texas Children’s psychologists encourage parents to talk about feelings, model coping and make sure that their kids are engaging in pleasant activities, instead of isolating themselves in their rooms or on social media. Families also are supported in making their home environments safer for children experiencing thoughts of suicide.

Children and adolescents brought to Texas Children’s Emergency Centers with disruptive and aggressive behavior primarily are those with developmental disabilities.

“Our kids respond to stress just like everybody else, including with a fight or flight response,” said Robert Voigt, MD, Chief of Developmental Pediatrics and Director of the Meyer Center for Developmental Pediatrics & Autism at Texas Children's Hospital, and Professor of Pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine. “Since many have trouble communicating, an increased level of disruptive behavior may represent their attempt at communicating the stress they are experiencing. With all the stress of the pandemic, many are experiencing an increased level of disruptive behavior, which is exceeding their parents’ ability to manage at home. Thus, many frustrated parents are taking their children to the ER for help.”

The Meyer Center evaluates children with the full spectrum of neurodevelopmental disabilities, from learning disabilities, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and mild motor incoordination to intellectual disabilities, autism and motor disabilities, including cerebral palsy and spina bifida. The Meyer Center also evaluates patients at high risk for developmental-behavioral disability, including former premature infants or those who have experienced other neonatal complications, children with congenital heart disease, and children with congenital anomalies or genetic syndromes, such as Down syndrome and Fragile X syndrome.

“Many of these children struggle with coping even with minor changes in routine, like driving a different way home from school. So imagine if your routine is as different as it has been during the pandemic, with schools changing their schedules week-to-week,” said Dinah Godwin, MSW, a licensed clinical social worker at the Meyer Center and Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at Baylor.

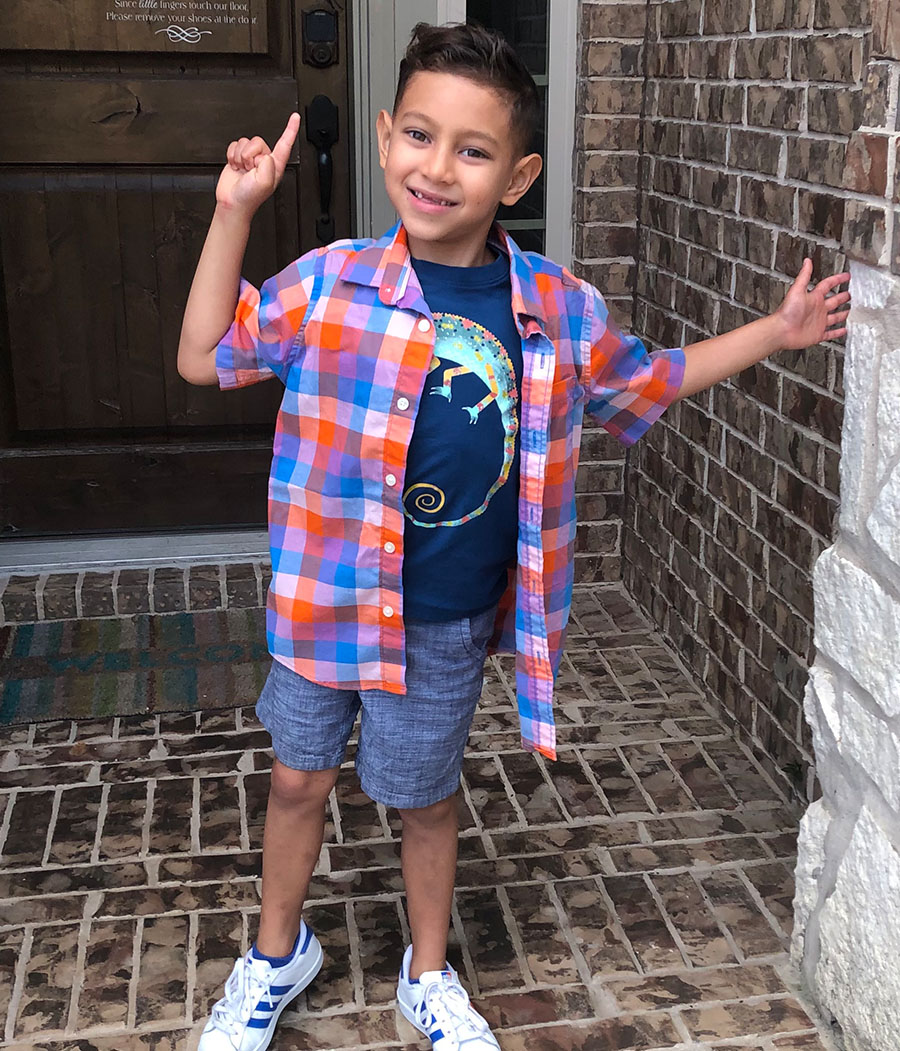

For example, changes in the school schedule and staff exacerbated the impulsiveness of Meyer Center patient Roman Shen, 7, and could have led to a tragedy. Roman has ADHD in association with Shwachman Diamond Syndrome, a rare genetic disorder that causes severe immune compromise.

The children were on the playground when Roman became upset one day. The aide assigned to several children, including Roman, did not respond.

When the principal came outside and yelled at Roman, “his fight or flight response went off,” said his mother, Nicole Shen. “He ran full speed toward the street with moving cars.”

Fortunately, several staff members managed to catch Roman before he reached the busy roadway.

Shen is grateful to live in Houston, where Texas Children’s specialists could diagnose, treat and advocate for Roman. In the United States, more than 19 million children and adolescents less than 19 years of age have disorders of development or learning. But there are fewer than 800 board-certified developmental-behavioral pediatricians in the country.

In December 2021, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD, MBA, issued a 53-page Advisory on Protecting Youth Mental Health. The advisory called for a coordinated response involving young people and their families, educators and schools, community organizations, and media and technology companies.

“One of the systemic gaps that COVID-19 has exposed is the gap in services and accessibility for kids with developmental differences. We have found that a lot of health professionals have not been trained on developmental diagnoses,” said Jennifer Cervantes, MSW, a licensed clinical social worker at the Meyer Center.

Meyer Center staff members have expanded family, community and professional education programs to highlight issues in the care of children with developmental disorders and resources to help families. They conduct in-person and virtual workshops and distribute an electronic newsletter monthly.

Co-chairing a new Behavioral Health Task Force are Dr. Price, Dr. Voigt and Kirti Saxena, MD, Chief of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at Texas Children’s and Associate Professor of Pediatrics and Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences at Baylor. The task force is assigned to help the department thoroughly develop the full spectrum of care from prevention to outpatient therapy to hospitalization.

Godwin expressed the optimism of the Pediatrics team noting, “We all believe that kids are resilient. With the right supports and the right guidance through this difficult time, our kids are going to be okay.”