A 14-year-old high school freshman noticed some lumps in his abdomen the night before he was scheduled to have a required physical exam for a school trip. An ultrasound was obtained. His doctor told him to go on the trip and that additional imaging studies would be scheduled at Texas Children’s Hospital when he returned.

Everything happened quickly after that. CT scan. Biopsy. Surgery to remove multiple tumors.

“When I came out of the operating room, my parents were reviewing a consent for chemotherapy,” remembers Michael Gleason, MD, MSPH. Dr. Gleason now is Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Hematology-Oncology at Baylor College of Medicine and Director of the Cancer Survivorship Program at Texas Children’s Hospital The Woodlands.

Dr. Gleason was diagnosed with Burkitt lymphoma, the most rapidly growing cancer of childhood. Burkitt lymphoma can double in size in 24 hours. Since chemotherapy targets rapidly growing cells, Burkitt lymphoma generally responds quickly to treatment. This was the case for Dr. Gleason, and his cancer was cured.

Fortunately, most children who are diagnosed with cancer in the United States today survive, with childhood cancer cure rates exceeding 80%. In fact, about one in 750 young adults is a childhood cancer survivor. There are more than 500,000 survivors of childhood cancer in the United States.

“It’s stunning,” said Baylor Professor ZoAnn Dreyer, MD, the Sidney L. and Donald F. Faust Professor in Pediatric Cancer Survivorship and Clinical Director of the Long-Term Survivor Clinic at Texas Children’s Cancer & Hematology Center.

Dr. Dreyer recalled that when former President George H.W. Bush’s daughter died from leukemia in the 1950s, almost no one survived that childhood cancer.

When Dr. Dreyer launched the Long-Term Survivor Clinic in 1988, she said, “The focus was primarily on cure and not much on late effects of treatment. People were just beginning to understand that survivorship was a big deal.”

Goals of the Long-Term Cancer Survivor Program at Texas Children’s Hospital are to:

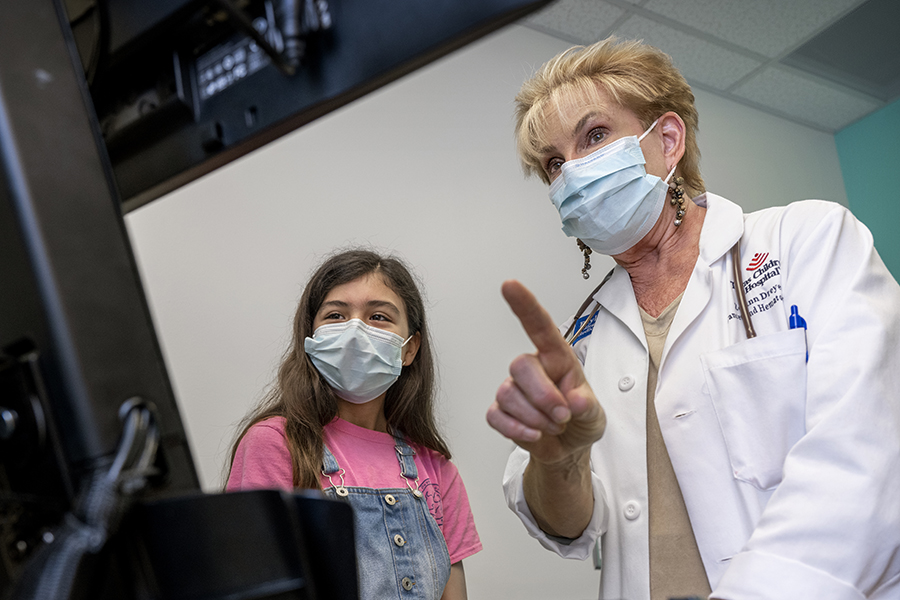

ZoAnn Dreyer, MD, Clinical Director of the Long-Term Survivor Clinic at Texas Children’s Cancer & Hematology Center, shows Passport for Care to a young cancer survivor. Some 45,000 survivors from more than 140 institutions across the country access individualized information through the internet-based tool.

ZoAnn Dreyer, MD, Clinical Director of the Long-Term Survivor Clinic at Texas Children’s Cancer & Hematology Center, shows Passport for Care to a young cancer survivor. Some 45,000 survivors from more than 140 institutions across the country access individualized information through the internet-based tool.

Most people are familiar with the nausea, hair loss and fatigue that often accompany cancer treatment, but they may not know about long-term or delayed effects of cancer and its treatment. An article in the New England Journal of Medicine reported that two-thirds of 20,000 cancer survivors surveyed nationally had at least one ongoing medical condition. For example, spinal injections for leukemia and high doses of radiation for brain tumors may lead to difficulty with learning. Other long-term effects may involve the heart, lungs, growth, hearing, thyroid and fertility.

One-third of childhood cancer survivors develop a severe, disabling or life-threatening chronic health condition within 20 years of completing therapy. After the age of 40, survivors have at least twice as many new cancers as someone without childhood cancer.

The Long-Term Survivor Clinic at Texas Children’s is one of the largest in the country, including patients from 18 states outside Texas and 13 countries outside the United States. Programs are conveniently located at each of Texas Children’s three Houston-area hospitals and in the Vannie Cook Clinic in McAllen, Texas, which is in the Rio Grande Valley.

Patients are referred to the survivorship program about two years after they complete their cancer treatment. Patients, typically seen annually, meet with a medical provider, a social worker, and if needed, a neuropsychologist and a financial counselor. Many other subspecialists are available (such as endocrinologists, cardiologists and pulmonologists), as needed for the care of individual patients.

The clinic is one of only a few providing care:

“By the time survivors hit 18 or 21, most programs send them on to doctors who take care of adults,” Dr. Dreyer said. “The problems that we see tend to crop up more in the late teens and young 20s. We see survivors of all ages, even in their 50s.”

No matter where they may live in the future, childhood cancer survivors can access readily available information through the Passport for Care. This internet-based tool contains information about the survivor’s cancer and treatment. It also provides each survivor and health care providers with individualized guidelines for follow-up based on national guidelines.

The Passport for Care is used by more than 1,500 survivors from the Texas Children’s Survivor Program and 45,000 survivors who are treated at more than 140 institutions across the United States.

“This is an incredible tool,” Dr. Dreyer said. “It’s also a model for the management of adult cancer survivors, as well as for children and adults with chronic medical conditions.”

Survivors also benefit from opportunities to meet with other survivors of childhood cancer. The Periwinkle Foundation helps Texas Children’s meet psychosocial needs of survivors. Through monthly social gatherings, educational sessions, or summer camp, the Periwinkle Foundation fosters a social network in a non-medical setting to provide peer support for an improved sense of wellness.

“I loved the camp experience so much that I went back as a volunteer for 10 summers,” said Dr. Gleason, who now is on the Periwinkle Foundation’s board of directors.

Although he already had thought about becoming a doctor because of his interest in math and science, Dr. Gleason credits his experience as a camp counselor for his decision to become a pediatric oncologist.

“To be able to see those kids grow up, have shared experiences and talk about our diagnoses is what convinced me that this truly is what I should do,” he said. “It also is helpful for young survivors to see somebody as their counselor who is five, 10 or 15 years after their own cancer diagnosis. It provides them with a good perspective about the future.”

In addition to providing support to current survivors, the Texas Children’s Long-Term Survivor Clinic looks to constantly improve care and survivorship through research. The clinic participates in clinical trials through the Children’s Oncology Group and has several National Institutes of Health grants. There are many important areas of research for survivors. Examples of ongoing survivorship research in the Texas Children’s program include studies about exercise tolerance, the aging process, and disparities in health care.

In 2020, Texas Children’s Hospital received the first $10,000 Children’s Cancer Cause Survivorship Champion’s Prize. The prize helped:

The program has grown from about 100 survivors the first year to nearly 2,500 now. Participants give the program high marks.

“It’s incredibly emotionally fulfilling when you see one of your patients that you treated six or seven years ago, and they come back to the Long-Term Survivorship clinic,” Dr. Dreyer said. “For them, it’s a landmark — they feel, ‘Our disease is behind us, and we’ve made it.’”