On June 11, 2022, the family of Knoxley Smith, then just shy of 6 months old, faced an agonizing decision. Should they accept that their son was not going to make it and start planning his funeral, as some doctors advised them, or fight for his survival?

Knoxley was born a “micro-preemie” — a baby born before the 26th week of pregnancy or weighing less than 28 ounces (700-800 grams) — at Minnesota Children’s Hospital. His premature birth resulted from severe intrauterine growth restriction, but Knoxley had already beaten the 5 percent odds of surviving birth. Weighing only 12 ounces as a newborn, he suffered from chronic lung disease, a result of underdeveloped lungs, and pulmonary hypertension, a condition in which the blood pressure in the lungs is abnormally high.

In children with pulmonary hypertension, it is difficult for the heart to pump blood into the arteries of the lung, where carbon dioxide is ordinarily removed and replaced with oxygen. This causes oxygen levels in the body to drop. The cause of pulmonary hypertension is sometimes unknown, but in most cases, including Knoxley’s, it is secondary to another medical issue.

Knoxley was intubated at birth and, over the next 172 days, experienced a tumultuous stay in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), alternating between intubation and Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP). Following a tracheotomy, his condition improved and his family thought he was turning a corner — but then came the diagnosis of pulmonary vein stenosis. With this rare disease, the veins carrying blood from the lungs to the heart are narrowed, preventing the heart from receiving oxygenated blood and causing significant complications.

Knoxley became extremely ill and started to deteriorate.

“The care team in Minnesota saved Knoxley many times over, but they lacked the expertise in his multiple diagnoses to treat him long term,” said Brenna Smith, Knoxley’s mother. “Our nurses and primary physician encouraged us to explore other options and told us about Texas Children’s. At this point, we had come so far, done so much and knew there had to be somewhere that could help Knoxley.”

The Smith family chose to fight at the one place they felt they could turn to for hope: The Texas Children’s Hospital Pulmonary Hypertension Center (PHC).

In June, Knoxley boarded a MedFlight to Houston in extremely critical condition, weighing 10 pounds and on a paralytic drip to keep his oxygen levels stable.

Throughout the U.S., there are very few formal pulmonary hypertension centers that offer comprehensive care. Of those that exist, the vast majority focus on care for adult patients.

Texas Children’s offers highly specialized, comprehensive care — from diagnosis to lung transplantation — in one of the largest pediatric pulmonary hypertension centers in the U.S. It is one of just eight comprehensive care centers accredited by the Pulmonary Hypertension Association.

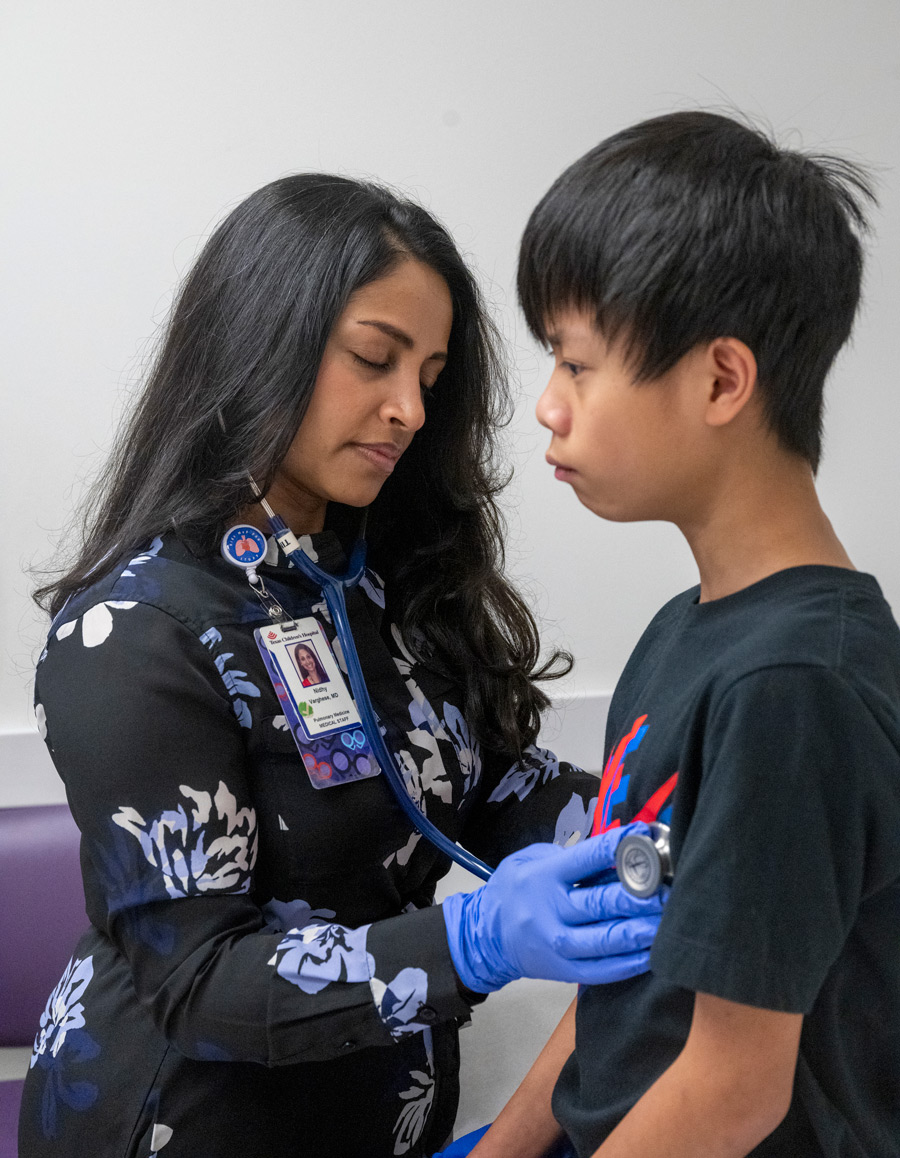

“The majority of general pediatricians will go their entire career without seeing a child with pulmonary hypertension,” said Nidhy Varghese, MD, Associate Professor of Pediatrics, Pulmonology at Baylor College of Medicine and Director of the PHC and Knoxley’s primary pulmonologist at Texas Children’s. “Assessing a patient with pulmonary hypertension and meeting their needs requires a lot of time and resources that non-specialized providers do not have.”

As a world-class institution covering every specialty involved in pediatric care, Texas Children’s has a distinct advantage in treating these patients. Not only do patients see a team of pulmonologists, but they also benefit from collaboration between these physicians and other specialists whose expertise is valuable to their unique case. These experts include cardiologists, pediatric intensivists, neonatologists, surgeons, pharmacists, palliative care providers, physical therapists and rehabilitation specialists, social workers, nutritionists and child life specialists.

Additionally, dedicated pulmonary hypertension nurse coordinators work very closely with patient families as a “front line” to the program by providing resources, answering questions and delivering caregiver education on an ongoing basis. Dedicated pulmonary hypertension advanced-practice providers deliver care in inpatient and outpatient settings and work with care teams to bridge care gaps during vulnerable periods for patients, including discharge, transfers and outpatient illnesses.

With such a robust care team dedicated solely to pulmonary hypertension, the breadth and depth of services enable complete, 360-degree care, elevating Texas Children’s compared to other institutions and attracting patients from across the U.S. and internationally.

Each year, Texas Children’s treats approximately 300 children with pulmonary hypertension of all types — a large number considering that it is an extremely rare diagnosis.

In the last four decades, the treatment for pediatric pulmonary hypertension has advanced significantly. Previously, only one treatment was available: a continuous IV infusion of Epoprostenol, a medication that lowers blood pressure in the lungs by dilating blood vessels. This medicine has a half-life of two minutes and is light- and temperature-sensitive. As a result, patients were connected to a specialized, covered IV pump around the clock, and had to carry ice packs to keep the medication cool.

Today, more than 13 therapies exist to manage symptoms, and these are often used in combination. The successful and safe treatment of patients with pulmonary hypertension requires great expertise and strong collaboration both within the medical team and between the providers and family.

“While many people may feel comfortable prescribing a pulmonary hypertension medication, fewer actually understand their pharmacokinetics and effects on physiology — and that is why getting care from an expert center can make a difference,” said Dr. Varghese. “We offer the optimal therapy for each patient, meaning that we tailor our approach based on the individual patient’s disease and risk factors. When patients do not respond as expected, we can anticipate and manage their condition.”

If these medications fail to work, surgical interventions, such as the creation of decompressive shunts, may be explored through the support of the Texas Children’s Right Ventricular Failure Program. In more advanced cases, lung transplantation is considered the ultimate therapy for patients who have exhausted all available treatments and experience disease progression or who are extremely unstable and need immediate intervention. In these cases, the Pulmonary Hypertension Center team works closely with the Texas Children’s Lung Transplant Program team.

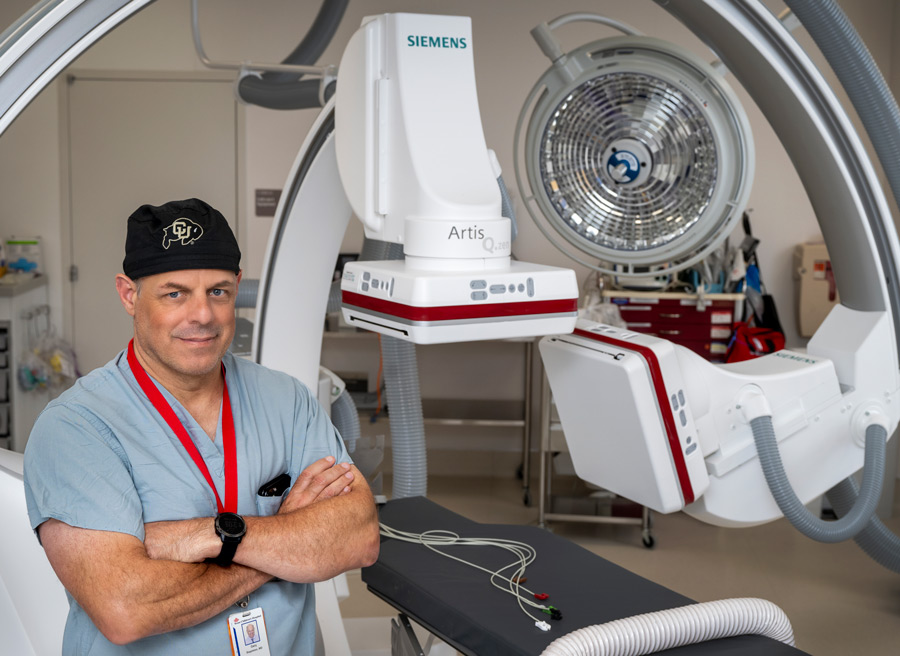

Knoxley’s family decided to move to Texas to be near his Texas Children’s care team, which also includes Knoxley’s primary cardiologist, Gary Stapleton, MD, an interventional physician with the Texas Children’s Pulmonary Vein Stenosis Program and Associate Professor of Pediatrics-Cardiology at Baylor College of Medicine.

“It’s been a major upheaval and lifestyle change,” Brenna said. “We were uprooted from home and family and lived in a hotel in the Medical Center for a few months. Our 4-year-old son was left with grandparents in Wisconsin a lot. But it was worth it because Knoxley would not have made it without Texas Children’s. I am so thankful we had the opportunity to come here.”

After spending his first 239 days in the hospital, Knoxley was able to go home to the house his family rents in the Houston area. Now stabilized, he takes several oral medications and is on constant ventilator support. His oxygen must be monitored regularly, and, if oxygen levels dip too low, he is re-admitted to the hospital. Knoxley also undergoes serial catheterization interventions every few months to assess the pressures in his heart and blood vessels and to intervene on his pulmonary veins.

“Going to the hospital is concerning, but at the same time, we are in a zone of safety here,” Brenna said. “Everyone is always checking on us. I am amazed at how all the clinicians work together and remain in constant communication. Knoxley’s case covers multiple departments, and every time we meet with a physician, they are up to date and know what is going on. I never feel like we are starting over.”

Pediatric patients with pulmonary hypertension can appear healthy, but they can often feel uncomfortable, short of breath, fatigued and unable to endure much physical activity. Wearing a pump constantly can attract undesirable attention from peers when these children want to simply fit in and feel normal. Medications can sometimes have unpleasant side effects, such as flushing of the cheeks and headaches. Though pulmonary hypertension is a chronic, lifelong condition, modern treatment can mitigate patients’ symptoms and greatly improve their quality of life.

For Knoxley, his ability to get off his ventilator long term is uncertain, but he is now able to start physical, occupational and speech therapy at home on an outpatient basis.

“Since coming home, Knoxley’s development has blossomed,” Brenna said. “He loves playing with his big brother and his toys, going for walks and taking baths in his baby tub. It is awesome to see all the new things he can do. Of course, his condition is not a steady incline, but more like a rollercoaster. But he is here and doing well.”

For Dr. Varghese, achieving these outcomes is a great joy.

“I love getting to be a small part of our patients’ stories,” she said. “These children have a life-threatening disease, and some have little hope at the beginning. But then they come to Texas Children’s, to a team that knows about pulmonary hypertension, and it is like coming home. It is a home that is built on trust and hope.”