The entire Texas Children’s Hospital team and Brent Kaziny, MD, the physician overseeing its emergency management and deployment of G7, are no strangers to disaster. Both have an extensive history of performing superbly in response to crises.

In his second month as a pediatric resident at Tulane University during Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Dr. Kaziny learned firsthand the importance of disaster management. After the city’s levees failed, Tulane Hospital, where he worked an on-call shift during the storm, lost electricity, and 80 percent of New Orleans flooded.

Dr. Kaziny helped evacuate patients and staff to other cities for four days. It became clear to him that the lack of evacuation and family reunification protocols and an absence of backup communications were significant hindrances.

When Dr. Kaziny came to Texas Children’s in 2012, the institution had built a reputation for preparedness during Tropical Storm Allison in 2001. Though most hospitals in the Texas Medical Center had to evacuate due to severe flooding and could not resume normal operations for months, Texas Children’s remained open and operational the entire time thanks to hospital leadership’s decision to install five basement-level flood doors one year earlier.

Dr. Kaziny became the first physician to lead the Texas Children’s Emergency Management Committee, whose membership draws from across the institution and meets monthly to plan for disasters. In addition to investing in critical infrastructure and technological improvements, Texas Children’s conducts annual drills to test disaster preparedness protocols and interfaces with physician leads of all clinical sections to confirm staffing and operational needs during emergencies.

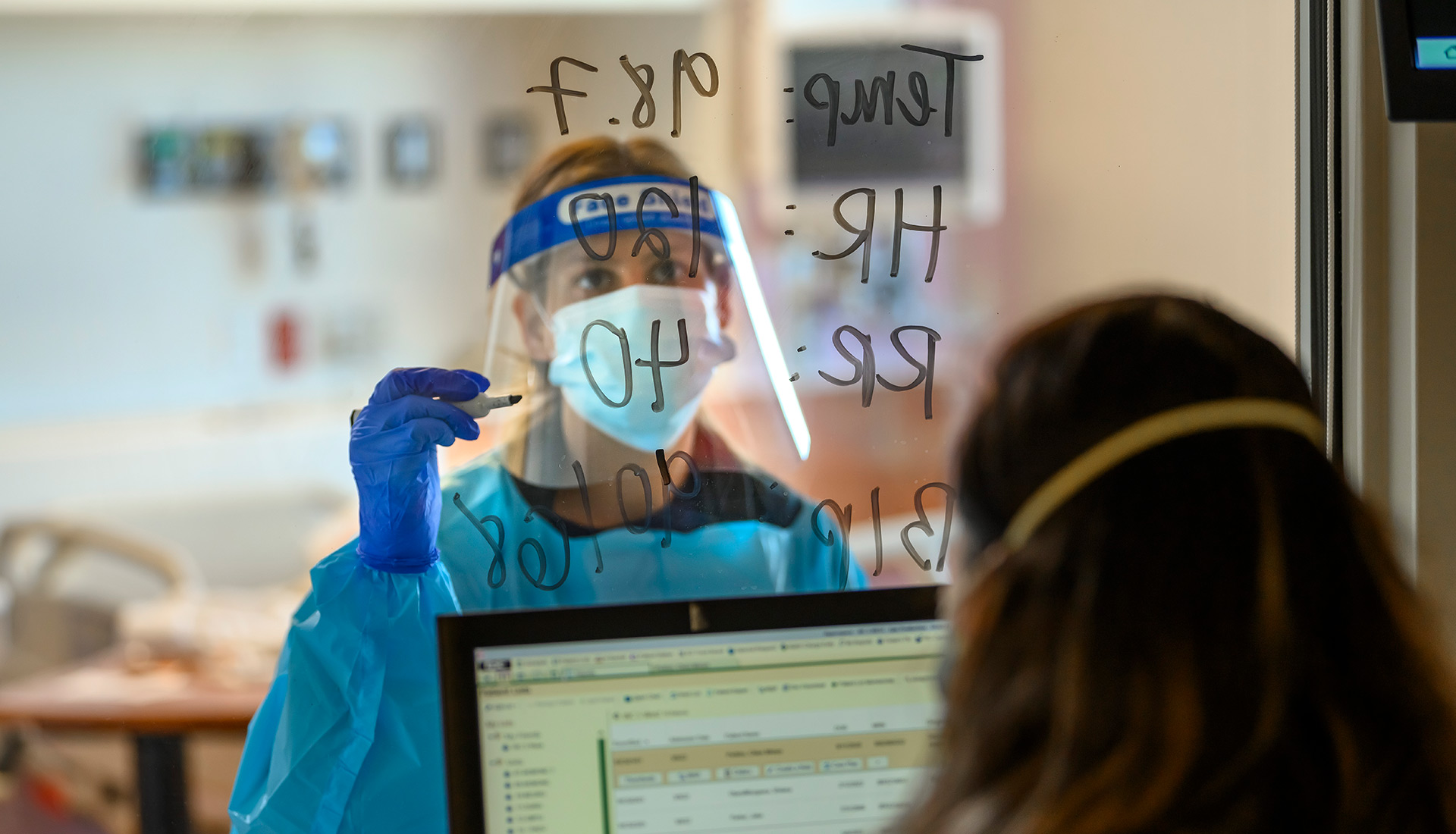

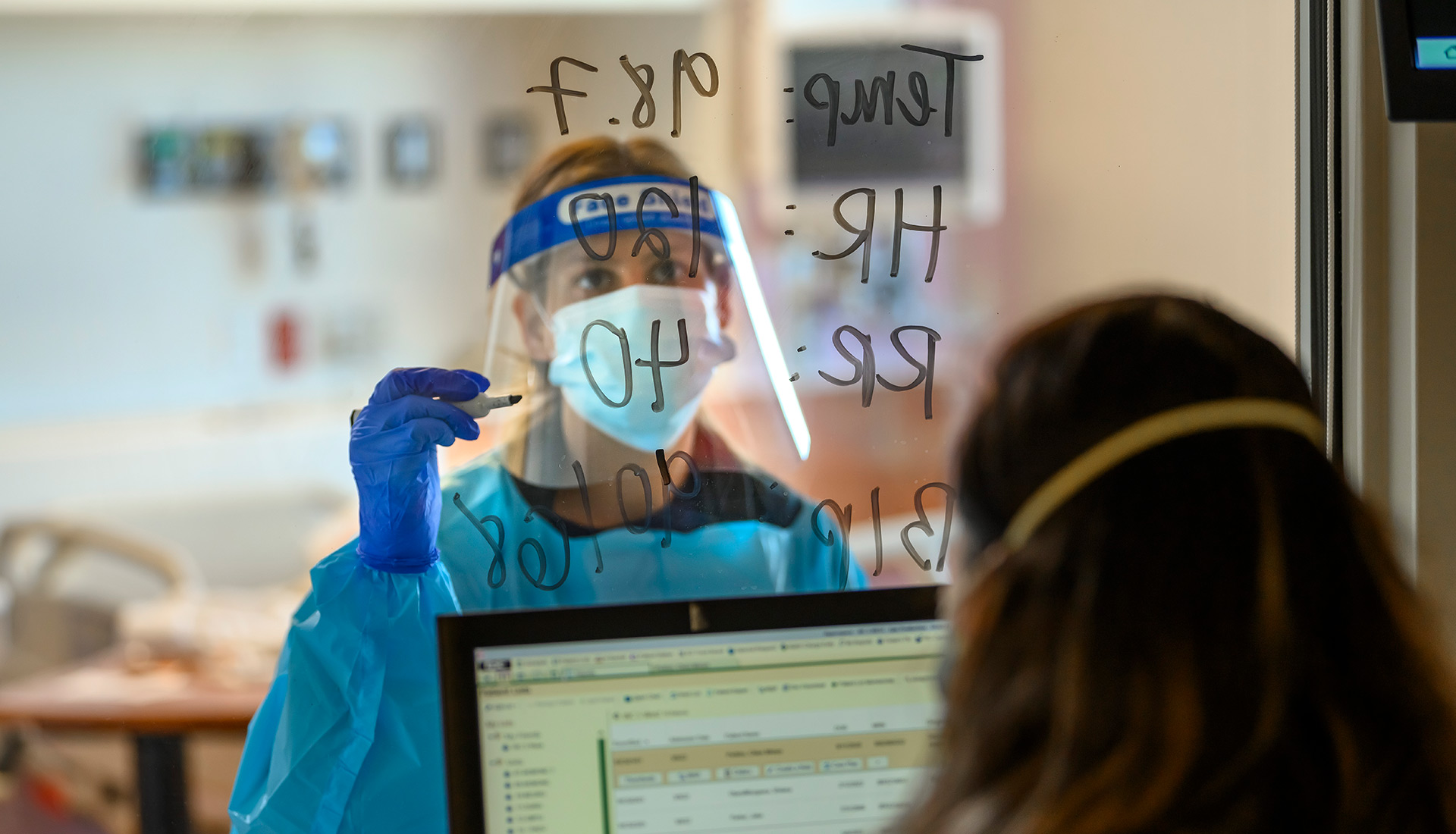

The Ebola crisis in 2014 inspired Texas Children’s to create the Special Isolation Unit (SIU) with Amy Arrington, MD, PhD, at the helm as Medical Director. The SIU is one of the few pediatric biocontainment units in the U.S. It was built to treat children with highly infectious diseases such as Ebola, MERS (Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome), SARS (sudden acute respiratory syndrome) and avian influenza (bird flu). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the SIU proved advantageous in treating initial patients and, further into the pandemic, managing the more complex cases.

During Hurricane Harvey in 2017, Texas Children’s served as an example of best practices in a storm. Well in advance, the institution:

As the G7 Pediatric Center of Excellence, Texas Children’s is proud to share its resources, tools, contacts and knowledge with other hospitals to aid in their preparations.

Children tend to be an afterthought in disaster planning — despite most people agreeing that children should be prioritized in emergencies.

One of the lessons the COVID-19 pandemic taught health care professionals is that the state of pediatric care in the U.S. is tenuous. Many children’s hospitals nationwide are underprepared for widespread disasters, from treating an influx of pediatric patients to delivering highly specialized care, obtaining critical supplies, maintaining operations, ensuring continuity of care and reunifying families.

Should children’s hospitals become overwhelmed in a crisis, there are significant shortcomings in the broader health care system. General hospitals that provide adult care are not equipped to care for children. They do not have deployable emergency teams related to pediatrics. Health care coalitions, agencies and government entities typically lack a pediatric perspective.

This is why the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR) awarded a $3 million federal grant to Texas Children’s Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine “to create and lead the Gulf-7 (G7) Pediatric Disaster Network as a Pediatric Center of Excellence.” The grant was issued in September 2022.

The goal of G7 is to combine pediatric expertise throughout the Gulf Coast region — breaking down the silos that often characterize the work of major hospitals and health care practitioners — to develop coordinated responses to disasters that impact children in highly specialized areas of medicine, such as:

G7 encompasses Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida and Puerto Rico — an area so broad it covers three Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA) regions. As the regional leader, Texas Children’s serves as a hub for all planning activities, knowledge and resource sharing.

“No one wants to build the ark while it is raining,” said Amy Arrington, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Divisions of Critical Care Medicine and Tropical Medicine; Medical Director of the Special Isolation Unit (SIU); and G7 Regional Medical Director and Co-lead of the Clinical Resources Domain. “The goal is to be prepared in advance so you can weather the storm when a crisis inevitably happens.”

“If you are a smaller hospital, where do you even start when thinking about natural disasters, pandemics or chemical exposures? At a minimum, you need budgets, checklists, processes, training and personnel to start these programs. At Texas Children’s Hospital, we have extensive resources and clinical capabilities at our fingertips. For other hospitals, creating these things takes so much time and effort that does not exist alongside competing priorities. Sharing what we know and have with others is a real gift,” Dr. Arrington said.

G7 is the third ASPR-funded region in the U.S., following the Western Regional Alliance for Pediatric Emergency Management (WRAP-EM), based at the University of California at San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospital, and Region V for Kids, based at Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital in Ohio.

“In creating these smaller regions within the U.S., we are keeping subject matter expertise local and focused on individuals in the pediatric health care field who deal with the same threats routinely,” said Brent Kaziny, MD, Emergency Physician, Co-director of the Disaster Domain for Emergency Medical Services for Children and G7 Principal Investigator at Texas Children’s. “There is no need to start from scratch or reinvent the wheel when blueprints exist for managing these threats successfully.”

On the Gulf Coast, examples of common natural threats include hurricanes, floods and tornadoes.

“I am often contacted by hospitals around the country for advice on a range of different resources. Usually, these individuals are unaware of someone in their own backyard who is an expert on the subject matter, and collaboration will be the key to future improvements,” Dr. Kaziny said.

Dr. Kaziny looks forward to this endeavor bringing new expertise to the table.

“In my past involvement with federally funded grants, it is often the same 20 people across the country who participate. I enjoy meeting new people who are equally invested in disaster preparedness and learning about subject matter experts in my region who have not been involved before but are now,” he said.

Texas Children’s works with seven federally funded partners in pediatric health care to improve disaster readiness:

“Eventually, once we get preparations in order at our partner institutions, we want to expand our work to smaller children’s hospitals and general hospitals,” Dr. Arrington said.

The ASPR grant funds a variety of disaster readiness activities at Texas Children’s and funded sites:

“If we can achieve one-tenth of what we set out to do this year, Gulf Coast preparedness to handle another emergency will be much improved,” Dr. Arrington said.