Ranked second in the country among children’s hospitals for 2023-2024 by U.S. News & World Report, Texas Children’s Neuroscience Center leads treatment, research and surgical intervention for children with both rare and common neurological conditions. Basic scientists and clinical research scientists leverage emerging technologies and invent new ones, while the Neuroscience Center provides lifesaving treatments for thousands of children every year.

Success in discovering the genetic causes of neurological diseases was not immediate for Huda Zoghbi, MD.

During her first year of medical school at the American University of Beirut, she slept in a sleeping bag on the floor of the ladies’ room when civil war broke out in Lebanon and made it too dangerous to travel back and forth to campus.

In her clinical practice as a pediatric neurologist, she cried many nights over the news she had to deliver to parents whose child had a disorder for which the cause and treatment were unknown.

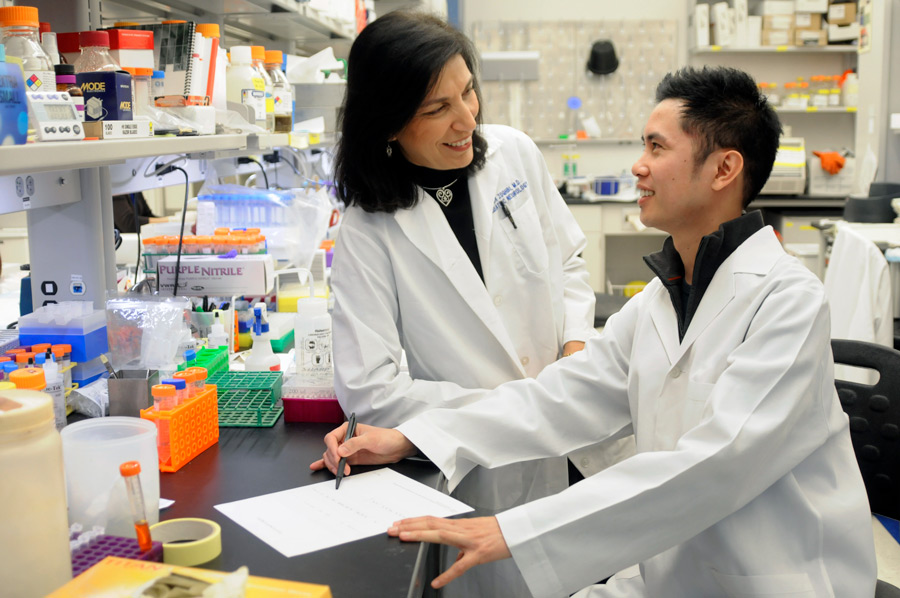

“I had to figure out what was happening to these patients and do something to help,” recalls Dr. Zoghbi, now Professor of Molecular and Human Genetics and Professor of Pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine, Director of the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute at Texas Children’s Hospital and a Howard Hughes Medical Investigator. In 2022, Dr. Zoghbi was named Research-in-Chief at Texas Children’s Hospital.

Her discoveries called for a combination of initiative, adaptability, perseverance and collaboration — with a dash of good luck.

Faced with the impossibility of finishing medical school amid fighting in Beirut, she convinced the dean and the head of admissions at Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee, to accept her, even though the semester had begun two months earlier.

She was determined to find the cause of Rett syndrome, a neurological disease resulting in a progressive loss of motor skills and speech. Faced with a lack of Rett syndrome patients in 1983, she enlisted volunteers from the Blue Bird Circle Clinic, Texas Children’s pediatric neurology outpatient clinic, to pull records of patients with key features of this developmental disorder, which primarily affects girls and is characterized by the patients wringing their hands.

In 1985, faced with a lack of research training, Dr. Zoghbi asked Art Beaudet, MD, then Chair of the Department of Molecular and Human Genetics at Baylor College of Medicine, to allow her to learn molecular genetics as a postdoctoral research fellow in his lab. Recognizing the technological challenges of Dr. Zoghbi’s Rett syndrome research, Dr. Beaudet encouraged her to study another disease that might be more tractable genetically.

Dr. Beaudet introduced Dr. Zoghbi to a family with spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA1) — an inherited degenerative and often deadly disease that causes progressive problems with movement and balance. After reading a paper by Harry Orr, PhD, Professor in the Department of Laboratory Medicine & Pathology at the University of Minnesota Medical School, about his search for the genetic cause of ataxia, Dr. Zoghbi initiated a scientific collaboration in 1988.

“Finally, on April 8, 1993, we both discovered the disease-causing gene on the same day,” Dr. Zoghbi said. “We had the pleasure of sharing the discovery and our data at an international ataxia meeting in Capri, Italy, that summer.”

Since the discovery of the gene, named ATXN-1, Drs. Zoghbi and Orr have continued to collaborate on studies of the origin and development of SCA1. “Our studies are continuing to help us understand the mechanisms driving disease, providing promise for future interventional studies in people,” she said.

Meanwhile, Dr. Zoghbi continued to collect data on Rett syndrome and had DNA samples from more than 200 affected girls. “The work, however, was one disappointment after another,” she said.

Finally, in 1999 — 16 years after Dr. Zoghbi first saw a patient with Rett syndrome — her postdoctoral fellow, Ruthie Amir, MD, found the genetic mutation that causes Rett.

“I had just opened the door of my house — returning from a trip to Lebanon — when the phone rang. I picked it up, and it was Ruthie. I asked her to bring her notebooks to my house, and she was there within the hour,” Dr. Zoghbi remembers.

Dr. Amir showed Dr. Zoghbi patient after patient with a mutation in the MECP2 gene. The mutation was not in the parents, accounting for the sporadic nature of the disease.

Since then, Dr. Zoghbi’s team has contributed to understanding Rett syndrome and is working on therapeutics.

They also determined that doubling MECP2 causes neurological problems in mice; others confirmed that in humans. The disease is known as MECP2 duplication syndrome or MDS. Her team found ways to reverse MDS in animal models, and preparations for clinical trials are underway with pharmaceutical companies.

With the help of her longtime technician, Alanna McCall, Dr. Zoghbi identified the mammalian equivalent of a fruit fly gene important for balance. Known as Atoh1, the gene in mammals is critical for hearing, balance, respiration and proprioception, the body’s ability to sense movement and location.

With international collaborators, Dr. Zoghbi’s lab has broadened its studies to other neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, autism spectrum disorders and Parkinson’s disease.

“Once we have deeper knowledge of the biology of the proteins involved in the disease, we can design much better prevention,” she said.

Their research accomplishments have resulted in many honors and awards. In 2022, Drs. Zoghbi and Orr received the prestigious Kavli Prize in Neuroscience, awarded for outstanding achievement in advancing knowledge and understanding of the brain and nervous system.

Kavli Prize Laureates are celebrated in Oslo, Norway, in a ceremony presided over by the Norwegian royal family. The Kavli Prize is a partnership among the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, the Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research, and the Kavli Foundation to recognize scientists in astrophysics, nanoscience and neuroscience for breakthroughs that transform understanding of the big, the small and the complex.

Dr. Zoghbi is not only broadening the horizons of current research but also of future research by mentoring more than 100 aspiring investigators, many of whom now have their own independent labs. Some are chairs of departments or chiefs of divisions.

“I see a very bright future, where what I’m passionate about is going to be multiplied at least 100 times in the next decade or two — to do great science that serves humanity,” she said.

Two types of researchers are needed, Dr. Zoghbi believes:

“I started my professional life as a physician and loved being a clinician, but I saw the difficulty in solving problems just with my clinical tools,” she said.

“Nothing is more rewarding than to be able to make a difference, to find the cause of a disease. Even if the treatment is not yet curing the disease, even if it’s just helping parents understand the diagnosis and helping with the management of some of the symptoms, that’s a step forward. The fields are moving fast to where more effective treatments will be coming in so many ways to help people. It’s really an exciting time.”